By Loring Danforth

Lewiston Sun Journal. Jun 9, 2019.

No one would ever mistake the Androscoggin Bank Colisee for the Great Mosque in Mecca. But for a few hours on the morning of June 4, the day Muslims around the world celebrated Eid al-Fitr (the Festival of Breaking the Fast), the Colisee was, literally, transformed into a mosque. The building where Muhammad Ali defeated Sonny Liston, the home of the Kora Shrine Circus and the site of so many Class A high school hockey championships between Lewiston and St. Doms, actually become a Muslim house of worship.

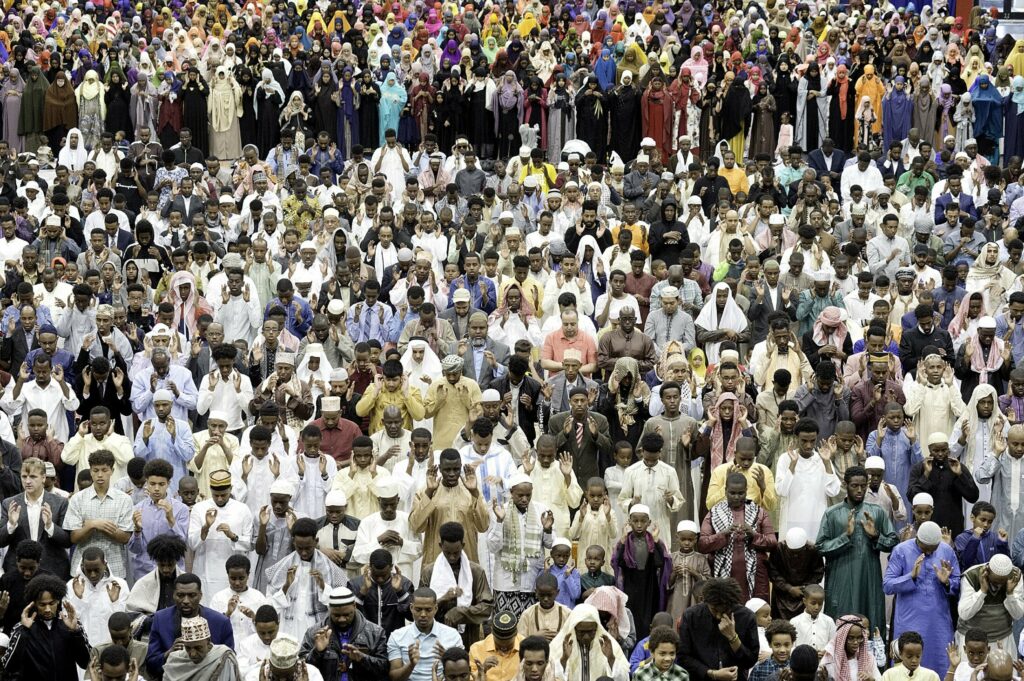

By 8:30 a.m. the Colisee parking lot was full. At the entrance to the building, administrators from the Middle School greeted their Muslim students and their families. Inside, women entered the rink from the south corner; men from a separate entrance on the north. Hundreds of shoes covered the floor around both entrances. When the service began, the rink was filled with some 1,500 worshipers, many of whom had brought their own small prayer rugs. The walls above them were covered with signs advertising Mailhot Sausages, St. Mary’s Hospital, and Bud Light.

Men sat cross-legged in rows filling the whole eastern half of the rink. They were dressed in clothing from all over the Muslim world — Somalia, Djibouti, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and America. Some wore tight-fitting, knitted skullcaps; others wore small embroidered cylindrical caps; still others wore red-and-white cloth head coverings draped over their shoulders or wrapped like turbans around their head.

Many wore long flowing robes in white, brown, tan and blue. Some wore dress shirts, jackets, and ties. A few elders had beards dyed red with henna. Young men were dressed in the latest American styles — baseball caps with their wide, flat brims facing backward, Tommy Hilfinger jackets and colorful Nike sneakers.

Women filled the western end of the rink from the blue line to the goal line. They were dressed more uniformly, but much more colorfully. The women were all wearing hijabs covering their hair and long flowing dresses in an astounding range of colors — bright yellows and pinks, incandescent reds and oranges, deep greens and blues. Beautiful black floral designs painted in henna covered the backs of their hands and wove up their wrists and forearms.

During the service, several imams, Muslim religious leaders, addressed the crowd in Somali and recited verses from the Quran in Arabic. They chanted the phrase “Allahu Akbar” (“God is most Great”) over and over again and called out to the faithful: “Praise be to God, Lord of all the worlds, the Compassionate, the Merciful. … You alone do we worship, and You alone do we ask for help. Guide us on the straight path, the path of those who have received your grace. … Amen.”

As they prayed, worshipers stood, raised their hands beside their heads, crossed their arms over their chest, bowed, knelt down and prostrated themselves, touching their foreheads to the ground.

When the ceremony ended at about 9:30 a.m., worshipers warmly greeted family and friends with handshakes, hugs and kisses on the cheek. In the parking lot, people gathered in groups to take photographs and exchange good wishes: “Eid Mubarak! Happy Holiday!”

Eid al-Fitr marks the end of Ramadan, the holiest month in the Islamic calendar that commemorates the revelation of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad. During Ramadan, Muslims fast from dawn to dusk. After the Eid service, they gathered at home for large meals and family celebrations.

The cultural richness and diversity of Lewiston delights me. I am thankful that the many Somalis who have made refuge in Lewiston have not “left their culture at the door.” They have kept their sense of family and their devotion to their religion, not to mention their considerable skills as soccer players. As a friend of mine once told me: “A garden with one kind of flower can never be as beautiful as a garden with many kinds of flowers.”

As I sat in the stands of the Colisee looking down at the hockey rink filled with Muslims praying as their religious leaders chanted “Allahu Akbar,” I was profoundly saddened by the thought that many Americans associate this Arabic phrase, meaning “God is most great,” with suicide bombers and violent acts of terrorism, rather than with the expression of religious devotion.

I was deeply moved by both the strangeness and the familiarity of the scene before me. This celebration was foreign to me in many ways, different from anything I had ever experienced growing up in America. But it also felt very ordinary, very familiar. I thought of my own experiences of Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter: new clothes, religious services and big family meals.

Claude Levi-Strauss, a French anthropologist, captured this paradox well: “When an exotic custom fascinates us in spite of (or on account of) its apparent singularity, it is generally because it presents us with a distorted reflection of a familiar image, which we confusedly recognize as such without yet managing to identify it.”

Media

“Islam comes to the Androscoggin Bank Colisee” at the Lewiston Sun Journal